There's a plethora of funders out there. There are national public funders such as VR (Swedish Research Council) in Sweden, DFF (Independent Research Fund Denmark) in Denmark, and DFG (German Research Foundation) in Germany. There are European funding schemes such as the European Research Council (ERC)and the Horizon Europe Framework Program under the European Commission. And, there are private funders and non-governmental organisations, such as the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation in Sweden and the Novo Nordisk and Lundbeck Foundations in Denmark.

Each funder has its own objectives, priorities, and criteria for evaluating and allocating funding. That said, despite their disparate scopes and missions, there are many commonalities in how funders evaluate proposals to fund. From the work that we've done at Elevate Scientific - where we have supported many researchers, teams, and centres over the years to apply for funding from a wide range of national, European, and private funders - I have found classes of evaluation criteria that come up time and again, irrespective of the funder. These classes align with those found by a systematic review of the literature on grant review criteria of peers.

What most funders prioritise

In general, for project funding (be it for a single applicant or team) funders evaluate proposals based on the merits of both the project and the applicant(s), with evaluation criteria for the project typically making up more of the basis for the total scoring of a proposal. The evaluation criteria I've come across can be loosely grouped into six overarching, general categories - five for the project and one for the applicant(s).

The evaluation criteria for the project typically apply to one or several of the key ingredients that most, if not all, applications for research project funding need to contain, including research question(s), state of the art, hypotheses, objectives, approach, research design, methods, preliminary results, risks & mitigation, ethical considerations, expected outcomes, impacts, project plan (including timelines), resources, budget, collaborations, and research environment.

Novel and originality

One common evaluation criteria that funders use is that of novelty and/or originality. The overarching consideration is whether and to what extent the proposed research constitutes a leap beyond the state of the art, producing new knowledge, theories, methods, applications, and other types of output that do not exist at present (funders typically does not prioritize funding confirmatory studies; this is not optimal, given issues with reproducibility in various research fields, but that is the priority of most funders at present).

The overarching criteria of novelty or originality are typically applied to several parts of your proposed project, for example, the research question, hypothesis, experimental design, methodology, or outcomes, and how these relate to the state of the art. More specific criteria related to novelty/originality can also occur, typically by guiding questions to reviewers. These often address specific parts of your proposal along the lines of the examples above. The more of these items that are truly novel and original and go beyond what exists in the current body of knowledge, the higher your proposal may be rated on originality/novelty.

Most funders also deprioritise research projects that only add smaller increments to the body of knowledge. Funders require you to produce substantial, large enough, incremental advances. How large, depends on the funder, the level of ambition it requires from applicants, and the amount of funding you seek.

Significance or importance

The second broadly occurring criterion that I've found funders to evaluate projects by is significance or importance. This can apply to several key ingredients in a grant proposal, including the research question(s), hypothesis, or expected outcomes.

Most, if not all, funders want you to tackle research questions and propose and test hypotheses that are deemed to be important and timely by the community. The space of possible research questions and hypotheses is potentially infinite, whereas research funding is not. Funders, therefore, make value judgments in selecting applications to fund - significance/importance is one of these value judgments.

This value judgment is typically not only applied to the justification of the project but also to its expected outcomes. Thus, novelty/originality alone is not enough to justify funding your proposal. The research gaps/questions/challenges that you plan to address and the outcomes from the project need to be considered important/significant.

Scientific quality/rigor and feasibility

Scientific quality/rigor and feasibility are the third and fourth criteria that I find all funders to use in various shapes. This is not surprising considering their centrality in the quality assessment of science.

Scientific quality/rigour is typically applied from a broader perspective to the way in which research is designed and conducted and can refer to the hypotheses (how they are formulated and justified), the experimental design, preliminary results, materials and methods, analysis, expected outcomes, and ethical considerations. The choices made to develop these items are (or should be) informed by the research question formulated and should rely on gold-standard approaches.

Feasibility is another non-negotiable for all funders because of its foundational nature for any project, not just research projects. This means that the project plan needs to be realistic (and planned in enough detail/specificity) in terms of structure, timescale, risks, resources, team, collaborations, and implementation of the tasks and approaches required to reach the project's goals.

Thus, whereas one could see the scientific quality/rigour criteria as evaluating the scientific dimensions of the project, feasibility evaluates the project's operational aspects. Scoring less than maximum on any of these criteria is often a deal-breaker for many funders.

Impact

The fifth evaluation criterion that I find to come up in various shapes in funders' assessment process is that of impact. This is a criterion that captures different ways in which funders evaluate the implications and the significance of the project's outcomes. I thereby distinguish between expected outcomes, which are produced within the project's scope and bounds, and impacts, which are 'downstream' outcomes generated as a knock-on effect.

The impact criterion is another type of value judgment that funders make when selecting projects to fund. It can entail impacts on a specialist or broader academic community, as well as on many other stakeholders, including patients, policy-makers, industry, and the general public. Which of these would be of interest to a funder depends on its specific objectives and priorities.

Applicant merits

In addition to the above five classes of evaluation criteria that funders use to evaluate projects, they also evaluate applicants based on their merits. This can pertain to several dimensions. Two fundamental components that all funders need to have satisfied is competence and expertise. Applicants need to possess the skillsets needed to take on the project.

However, many funders evaluate based on more than skills and expertise. Some make value judgments based on applicants' track record in producing what is perceived as ground-breaking research advances. Yet for other types of funding, there may be requirements to demonstrate leadership skills, reputation in the community (for example, through awards or being elected to selective positions in reputable scientific organisations), ability to manage large projects, or access to a broad professional network.

Finally, and particularly for early-career researchers, some funders evaluate specifically evidence that points to the applicant being able to conduct research independently.

Insights from a systematic review of grant review criteria

The above criteria overlap with those identified by a systematic review of

studies in grant review criteria of peers that I recently came across. Here,

the authors performed an analysis of 12 studies on grant peer review criteria,

using a four-component analytical framework:

- evaluated entity - the object to be evaluated, for examples the grant application or parts thereof, such as the research question, project plan, applicant CV.

- evaluation criteria - the dimensions along which an entity is evaluated, e.g. originality, relevance, soundness, and feasibility.

- frame of reference - benchmark against which an entity is compared, indicating the value of an entity on a specific evaluation criterion (for example the 7-grade scale that the Swedish Research Council uses for evaluating several evaluation criteria).

- assigned value - that an entity receives in a frame of reference of an evaluation criterion (in other words the grade/rating a project plan, CV or other part of a proposal would receive for a specific evaluation criterion.

Using this framework, the authors set out to answer the following questions:

"1) What entities are being evaluated in grant peer review? 2) What criteria are used? 3) Which entities are evaluated according to which criteria?"

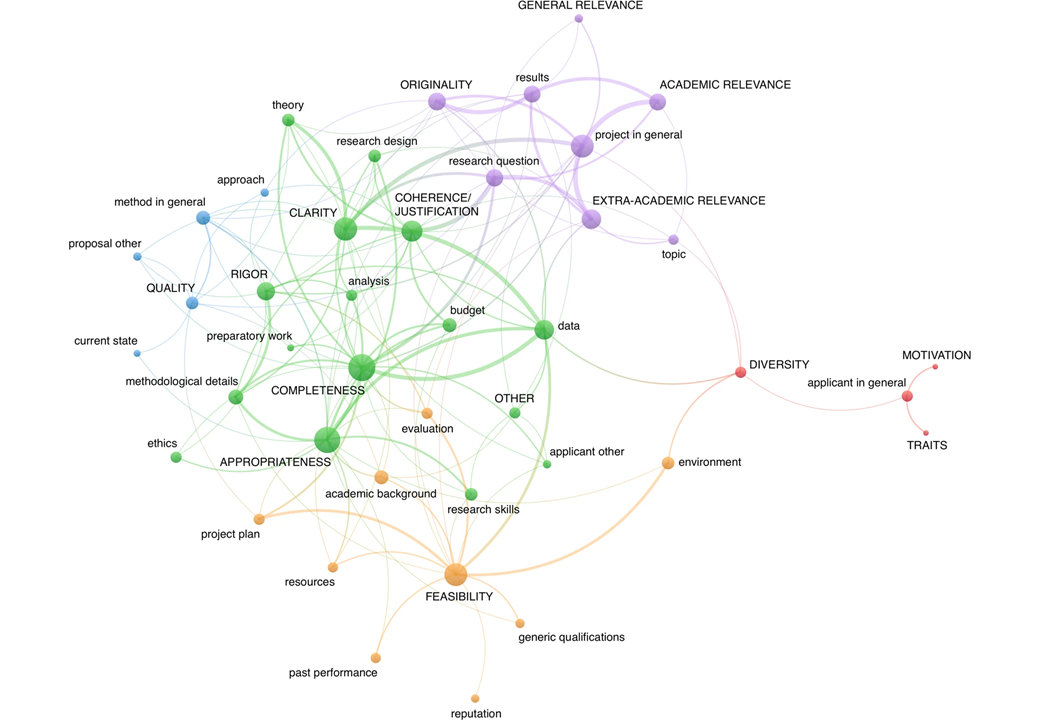

They found that the project is the most important entity, with the CV playing a comparatively minor role. This is in line with my experience for most project grants (which is also the scope of this study). For the project, they identified 19 sub-entities overlapping with my own (project in general, current state, topic, research question, theory, approach, preparatory work, data, ethics, method in general, methodological details, research design, evaluation, analysis, results, budget, resources, project plan, other).

In turn, they found eight sub-entities for the applicant, again many of which overlap with my own (applicant in general, generic qualifications, research skills, social skills, academic background, past performance, reputation, other). Finally, they identified one sub-entity for the environment, called research environment.

The authors identified 15 evaluation criteria. The six most frequent were extra-academic relevance, completeness, appropriateness, originality, feasibility. These were used to evaluate the main entities applicant, project, and environment. Originality, relevance (general, academic, on-academic), rigor, and coherence/justification were exclusively used to assess the project. Motivation and traits were solely used for applicant. Quality, clarity, completeness were used with both project and applicant.

They further performed a network analysis (Figure 1) to investigate how the evaluation criteria (all-capitalized words) were connected to different entities (lower-case words). As is my own experience, evaluation criteria are applied across multiple parts of a proposal (which the review authors call entities).

Lessons for grant writing

Understanding what funders want and how they evaluate grant proposals provide valuable insights into what information needs to be included in a grant proposal to maximise the likelihood of securing funding.

After all, a pre-requisite for any grant proposal for project-funding to be funded is that it is clear, complete, and coherent with respect to:

- why the research is needed?

- what the applicant wants to do?

- how the applicant wants to do it?

- what outcomes are expected?

- why these outcomes would be desirable and important?

- why the applicant would be best placed to conduct the research?

- why the research environment that the applicant is embedded in is conducive to realize the project?

Knowing these common evaluation criteria and key ingredients that all grant proposals need to contain is a vital stepping stone for understanding funders and writing successful grant proposals.

The next step is to research the specific funder you're interested in targeting.

Then, equipped with this background information, I typically advise researchers to spend considerable time in mapping out the key ingredients for the envisioned project (including the items mentioned in this article) and frame it for the specific funder (here, our own PAOI® framing method can be useful).

Only thereafter is it meaningful to put pen to paper, and draft the proposal text.

Thank you for reading! Share within your networks. And do let us know your comments, questions, or suggestions for topics you wish us to cover in future posts.

Features: everything in our on-demand, self-paced e-course + live sessions with Q&As and discussions (all courses), and exercises/peer-to-peer feedback (optional add-on).

We offer bespoke courses, course environment, and training of your staff in managing the LMS, to enable offering our courses to all of your researchers and staff in walled-off course environment that you control access to.

Features: everything in our on-demand, self-paced e-course + live sessions with Q&As, discussions, exercises, peer-to-peer feedback (optional add-on), individual feedback from instructor (optional add-on).

We offer bespoke courses, course environment, and training of your staff in managing the LMS, to enable offering our courses to all of your researchers and staff in walled-off course environment that you control access to.

Features: everything in our on-demand, self-paced e-course + live sessions with Q&As, discussions. Optional add-ons: exercises and assignments, peer-to-peer feedback.

We offer bespoke courses, course environment, and training of your staff in managing the LMS, to enable offering our courses to all of your researchers and staff in walled-off course environment that you control access to.